WeWork And Adam Neumann: Scam or Genius? 5 Lessons Learned From Their Rise and Fall

5 lessons for entrepreneurs and investors learned from the rise and fall of WeWork and of its headline-grabbing founder

WeWork And Adam Neumann: Scam or Genius?

In this article I'm going to share 5 lessons both startup entrepreneurs and investors can learn from the rise and fall of WeWork and of its headline-grabbing founder.

A Crazy Journey

WeWork's journey has been an exhilarating roller coaster so far.

From an obscure start in 2018 New York, as the successor to a co-working space fit-out project called Green Desk, to its wild public listing in 2021.

All along two things have remained constant:

- The business has been losing money ─loads of money.

- The business has managed to fetch valuations comparable only to Silicon-Valley backed tech unicorns.

But by now everyone has it clear: WeWork is not a tech company. It is a commercial real estate management company. Yet its journey has been just like that one of a venture-backed startup: receiving VC backing from its early phases and expanding, within a decade, to become a global corporation.

This weird combination of identities made some define WeWork as a laughable investor fraud. But then again its shares rose when it finally listed via a SPAC merger.

WeWork and me

In 2019 I become a WeWork member myself. I organised some of my London tech meetups in one of their offices and was bamboozled by their increasingly skyrocketing valuation and seemingly unrestrained acquisition mania.

Meanwhile one of his two co-founders, Adam Neumann, achieved celebrity status. Hitting headlines with polarising statements, growing his wealth to billionaire levels thanks to his large ownership of WeWork stock, and being at the epicentre of a failed IPO attempt in 2020 that costed him his job as the CEO of the company.

It always "felt easy" to say that, as an investor, I would never be like "those idiots" who plunged billions at a real estate company dressed up like a tech startup.

It was almost like an easy ice-breaker with fellow software developers and entrepreneurs to drop the line "Even startups eventually have to make money if they are to survive... Unless they are WeWork".

But then again: was it that simple?

Was the whole 10+ year journey just a gigantic Ponzi Scheme? Or was there something else in it? Were there any lessons to learn?

Then the Billion Dollar Loser came out to portrait this epic raise and (relative) fall.

A couple of months ago a friend and partner at a listed VC fund in London recommended it to me. So I read it.

My starting position was that of someone prepared to discover how a founder could "play" VCs to raise money at his leisure. The book narrative was that of a journalistic enquire looking to "expose" a cult that took a bad turn. Yet, despite all this, by the end of it, I was left with a much more neutral stance on the whole matter ─as well with at least some genuine sense of respect for all that the WeWork's founders achieved with sheer willpower.

Today I'm writing about 5 Lessons I've learned by reading this book, as someone who's been and still is going through the pain of building a business. As well as someone who sits on the other side when deciding to invest (or not) in a startup team.

TL;DR

Lessons for fellow entrepreneurs and investors:

- Embrace Uncertainty and Failure as Steps Towards The Billion Dollars

- A Grand Vision And The Willingness To Fight Hard For It Are Crucial

- Confidence and A Mission-Driven Attitude Can Move Mountains

- A Blitzscaling Mindset Is A Competitive Advantage

- Too Much Is As Bad As Too Little

The Lessons

1. Embrace Uncertainty and Failure as Steps Towards The Billion Dollars

Adam tried his hand at being an entrepreneur with a baby-cloth company before WeWork and gave it his 100%. He embraced his failure to graduate in order to focus on this company and toured the US to pitch the product in trade shows. He worked into the night and pushed his few employees to the limit, but eventually even this one failed.

Adam's co-founder Miguel also missed the chance of building a big startup. But he actually did build a successful tech-based business: a website helping people learning English. The problem of that company was that it became a profitable small enterprise that did not have a larger-than-life vision and could not scale.

Not only it did not raise large VC backing, but it got stuck in a state where it no longer provided a stimulus to Miguel's creativity. He was passionate about architecture but had no work experience, so he sold his stake, left everything and took a job for $10/hour to chase his dream.

When Adam and Miguel first tried out something in the real estate world together, they partnered up with a landlord to create a coworking space from a large empty building: Green Desk. They eventually realised just fitting out their financier's office spaces was not the way to build a billion dollar business, so they sold their shares of the project back to that landlord. This small success together gave them most of the experience and confidence (as well a couple of hundred thousand each) to launch a much more successful company after that.

According to data from Super Founders a founder with a previous startup failure was nearly twice more likely to reach a $1 billion valuation compared to a first-timer. A founder with a previous exit, even a small one, had even higher chances: more than three times those of a first timer!

As the author of that book, Ali Tamaseb, found out:

The best preparation for starting a wildly successful company is founding a startup... If you have never started a company, the best preparation for doing so is to start something, maybe a club, a side hustle, or simply selling something online...You might get to your billion-dollar outcome on your first try, but the data show that it’s more likely to happen on your second, third, or tenth. What is important, though, is to keep building until your luck comes through.

Now, the line between embracing uncertainty and blind faith can be fine and hard to draw. But dancing around its edges can also help in negotiation. Brinkmanship and the self-belief to call off a "chicken" play are powerful weapons if used with care.

Adam, for example, pulled off several major wins by avoiding to bend over to famed investors and, instead, "playing the investment game by his own rules". In 2013, for example, he turned down an offer from Goldman Sachs that would have valued the company at $220m. WeWork was bleeding cash to death by the founder kept on fundraising with a proud ask. Eventually they closed a round for $440m led by DAG Ventures. Double Goldman's valuation.

Could have WeWork gone bust then, if the hard-nosed approach had not worked out? Yes. However, as John Sculley (ex Apple CEO) once said:

If you are always playing it safe and you are not failing, there is a high probability that you are not doing anything important.

2. A Grand Vision And The Willingness To Fight Hard For It Are Crucial

Securing the first WeWork location, 154 Grand Steet, SoHo, Manhattan, was not easy and it required both identifying a problem to solve and pushing hard to implement a viable solution. The two founders had to find a property in a terrible state and a landlord who struggled to make money from it, as well as bargain hard to get both a cheap lease and contributions towards refurbishment costs.

However, identifying a niche to start a business from and fighting to get it going on favourable terms are not sufficient to build a scalable company.

You also need the vision to build something greater that what you can deliver today.

Adam and Miguel had it clear that they wanted to position their company as more than just an office rental business.

When WeWork opened in February 2010, their business development strategy was substantially different from traditional real estate management agencies.

They did not offer square meters nor desks up for lease, even if that was ultimately the product. They also did not target traditional office leaseholders (i.e. traditional established companies). They, instead, borrowed the edgy design and flexible leasing terms from Green Desk and other independent coworking spaces, which were starting to pop out as a novelty due to the recent financial crisis. They then cranked the "boldness" knob up and added community "activities" like parties and ice-breaking sessions and a "club-like" feeling to the customer experience. They pitched tenants the value of being part of a network of like-minded startup and freelance entrepreneurs. Finally, they stopped calling their tenants "tenants" and instead starting to referring them to "members". The branding exercise may have been a marketing stunt, but Adam and Miguel worked day and night to standardise the model, so that it could be later repeated in a scalable fashion.

WeWork was officially born: a mixture of bold vision and hardened skin from two founders with absolute confidence in their own capacity to build something greater than the sum of its initial parts.

In later years, this grand vision also helped them shape their pitch to investors, customers, as well as staff. WeWork wanted to be more that "just square meters". They wanted to be perceived as some kind of physical social network.

After a profitable year in 2012, the company even managed to bring on board investors that traditionally backed tech companies, such as Benchmark, in Silicon Valley. Benchmark's partner Dunlevie stressed the importance of a "founder's vision" by investing and stating "Let's give him [Adam] some money. He'll figure it out."

3. Confidence and A Mission-Driven Attitude Can Move Mountains

WeWork in the early days could not pay high salaries. This is something most startups suffer from. In its early days, since it did not have a tech background, it neither had stock options ─the founders would introduce them only later, when WeWork's path started to look increasingly like a venture-backed startup.

However, people often left jobs that were better on paper to join a company with a strong sense of purpose and an exciting journey of growth.

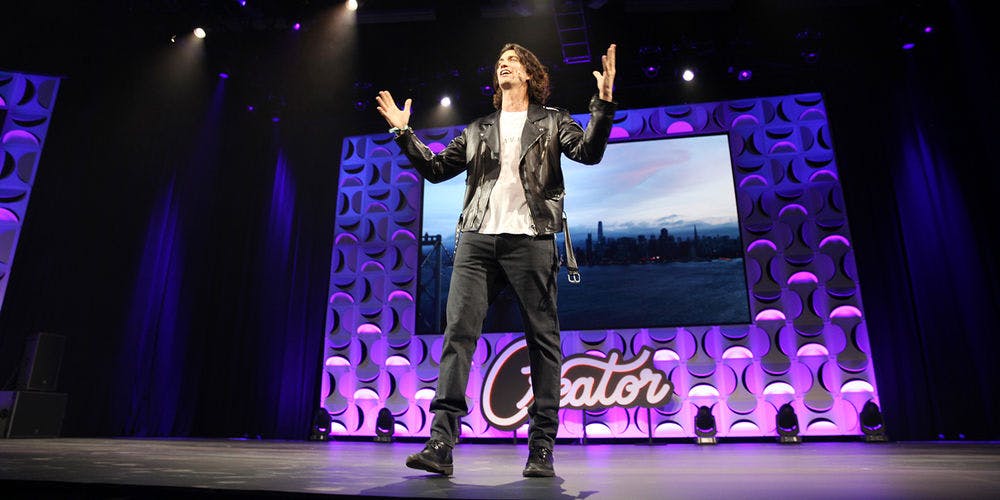

Most of this "sense of purpose" came from the inspiring words and confidence exuded by Adam, who had no reserve in telling everyone he was on a journey to build a $100 Billion business and become a bigger leaseholder than JPMorgan in New York.

Adam managed to rally people behind him thanks to his storytelling ability. He could make them envision a worldwide brand of offices that merged the flexibility of coworking and the community feeling of a hipster members' club.

This helped WeWork attract loyal employees who'd be happy to help out in loosely defined roles, as well as unpaid interns eager to learn valuable startup skills in exchange for their time.

On top of selling their vision in a "ballsy way", Adam and Miguel worked their arse off staying long hours in the office and even doing manual work themselves in the early days. This created a hard-working culture that pushed everyone to work harder and longer than they would at a typical 9-5 job.

Whilst Wideman, the author of Billion Dollar Loser, clearly paints this environment in a negative tone, the reality is that startups are hard work. Successful, hard-working founders can't build world-changing corporations alone. Their early employees need to be as committed as them for the enterprise to launch and scale successfully in its early stages. WeWork achieved this by selling them the business vision with confidence and by regularly rallying them in pep meetings and community events.

As a WeWork employee would comment:

Adam would put $100Bn in the deck, so he would end up getting 1Bn. You shoot for the moon and land higher than anyone else.

Even the body language and physical presence of a founder can help. According to another employee, Adam had developed a powerful capacity to stare people into their eyes and exude confidence with such a gaze. She said "it's what I imagine it feels like to have Julius Caesar stare at you".

4. A Blitzscaling Mindset Is A Competitive Advantage

Blitzscaling is a business concept and a book written by Reid Hoffman (LinkedIn Co-founder) and Chris Yeh. According to Hoffman:

Blitzscaling is what you do when you need to grow really, really quickly. It’s the science and art of rapidly building out a company to serve a large and usually global market, with the goal of becoming the first mover at scale.

Despite notable exceptions, taking a domineering role in a market by growing fast normally requires external capital injections. WeWork wanted to Blitzscale from the early moments: literally since the moment it proved the concept by filling up their first location. In fact, since filling up their previous work: Green Desk. Now, because WeWork operates a real estate product, it needed loads of cash.

Adam was fast to realise that he needed funding to fuel his ambitions and that funding is best secured not only by knowing "what to say" to investors, but also by "who" you know in the first place. He moved to posh NY neighbourhood of the Hamptons despite a still tight budge by taking a "leap of faith" on his business. He then worked hard from day one to grow his personal rolodex of contacts. He asked family friends, friends of friends, as well as early smaller investors and business acquaintances for introductions to other potential investors. In just over 2 years, he had managed to secure $7m worth of equity funding, giving him an early "unfair advantage" over the competing independent coworking spaces.

Another aspect of the Blitzscaling mindset the cofounders displayed from the start was their pursuit of "growth hacking on steroids" through early branding and positioning as a "growth story". No even 1 year after opening the first location, and with new ones only barely in discussion at all, the 2 cofounders already had virtual projects ready to show investors of what new locations would look like in New York and San Francisco. They used these to project WeWork as the "faster growing coworking operator" in America and get a keynote slot at Coworking Europe 2011. From there, Adam mixed a "peer-to-peer" advice speech with rhetoric more suited for an investor pitch.

In a nutshell: at WeWork they were "going for it" from day one.

Furthermore, Wework soon started implementing systems and rule-books to power its rapid expansion. This contrasted the very early phases where what counted was the charisma, hard work and inventive of its founders.

The goal then moved up even further: from being a physical social network to a worldwide "Space as a Service" accessible in any big city on the planet.

5. Too Much Is As Bad As Too Little

If you are a realist or a sceptic, you might be puzzled by my article by now. Am I saying WeWork is a good company we should take as a model? Hasn't it also lost a huge amount of value before going public, lost billions in revenue, risked bankruptcy, and got involved into stories of employee harassment, lawsuits, and bad management?

Well, that too. I'm am far from a WeWork "convert". I did not long after the listing and am not planning to do it any time soon either. However, we should not ignore the things it did right. At least in terms of being a business vehicle to channel its founders visions into becoming a corporate reality. It also fostered changes in the world of office leasing for startups and small businesses. WeWork's legacy actually helped increase the standards that a small team can expect from a shared office space. It also helped spread the concept of flexible co-working on flexible membership-like terms. This has, in general, made work time in the office for startups more affordable and enjoyable. Competitors took inspiration, which in the end was good for the end users.

Besides, WeWork's story can also teach us because of where it went clearly wrong.

With increasingly faster and bigger rounds of founding, the company's management lost track of reality. Their vision turned from being a propelling roadmap to a reality distortion field.

The company started to build technology it did not have a purpose for and to acquire companies that did not always fit with their business. Rather than helping the company achieve its mission faster and build a moat against competitors, too much cash too fast distracted the founder and created too many unrealistic expectations.

The founders also started to feel untouchable. Adam in particular let his ego run wild and parties, drugs, alcohol and arrogance got in the way of shaping a sustainable venture.

On a business side, the systems Wework started to implement were left incomplete and inadequate for the scale the company had reached thanks to the continuous rounds of financing.

Howard Schultz, the former CEO of Starbucks, told Adam to "slow down a little" and iron out any structural business problems before continuing breakneck expansion. Adam ignored the advice.

The extremes took over other sides of the businesses too, such as HR. Where the ruthless but potentially effective culling of the less productive bottom of the company staff became a systematic laying off of as much as 20% of the employees per annum. From being efficient, the environment started to become toxic.

The company even forged its own metrics to explain away mounting losses. One of the most infamous ones is probably the "Community Adjusted EBTDA ". A metric that turned a loss of nearly a billion in a profit of several million by removing costs such as marketing and admin.

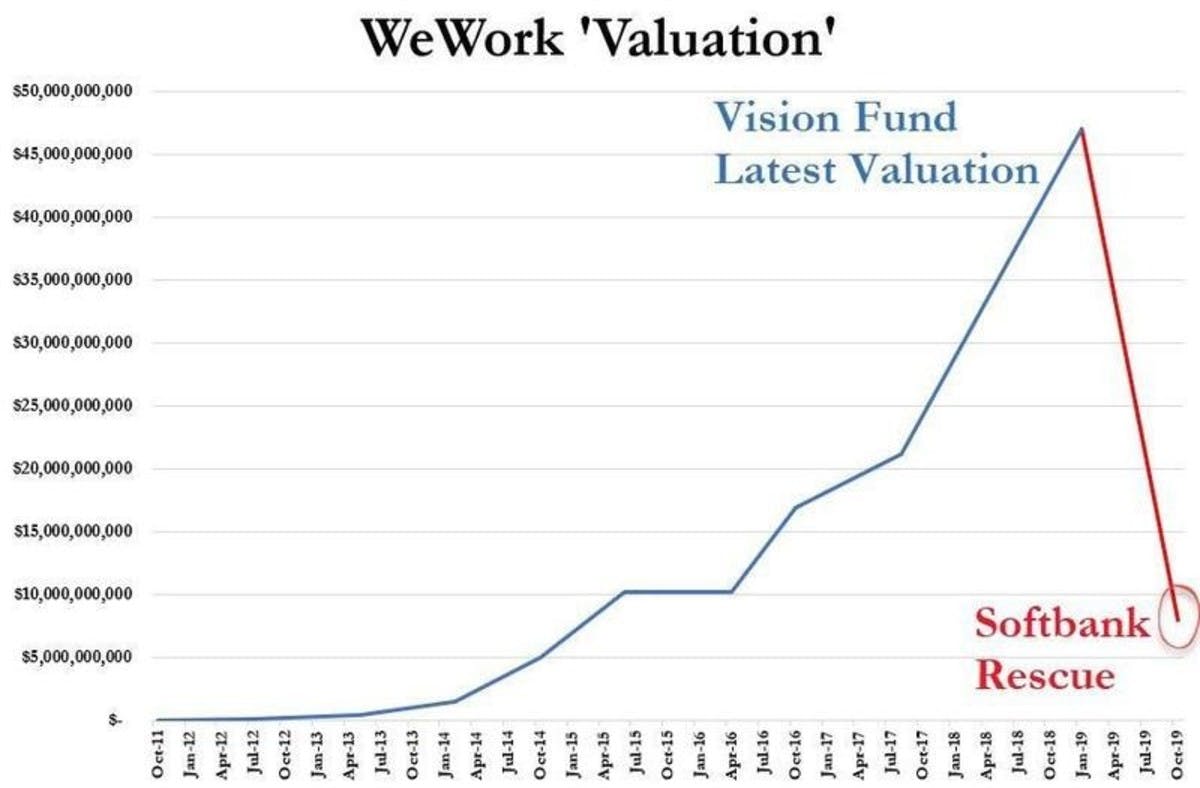

The situation only worsened as the bets investors were taking on pure speculation and gut feelings continued to increase. Eventually the infamous Softbank entry with billions over billions poured into the company, made everything that was bad even worse.

Concluding Thoughts

The rest is pretty much history.

After spectacularly failing an IPO and having its valuation slashed, WeWork pushed Adam to give up his super-voting rights and resign. Miguel left soon after.

Allegedly, Adam keeps a card on his desk to remind him of the reckoning that the WeWork fall caused. Listen. Be on time. Be a good partner.

Neumann told up to the CNN that: as more high-profile investors came on board and the valuation increased, it "made me feel that whatever style I was leading at was the correct style at the time. At some point [it went to my head]. I think the moment you lose focus on really the core of your business and why this business was what it meant to be."

Scam or Genius?

The jury is still out on that one.

They scaled in 10 years to become a brand name in cities across the planet and surpassed industry incumbent Regus in yearly revenue.

They also lost $2Bn in Q1 2021 alone.