Venture Capital History ─VC is Fuelling Innovation Since Renaissance Florence in 1400

A History of Venture Capital as an Engine to Promote Enterprise, Wealth Spreading and Innovation

A Backward-in-time Journey...

The journey to rediscover the whole history of Venture Capital starts right here in Europe, right now.

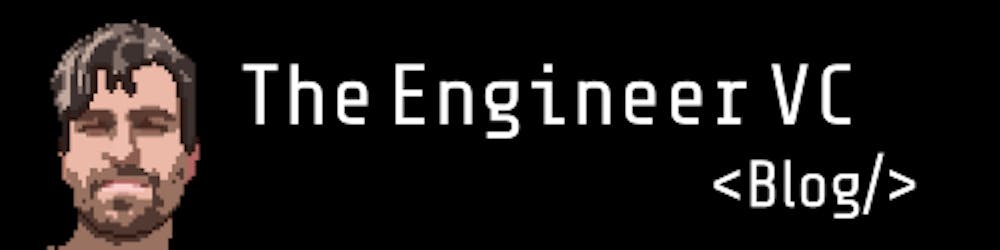

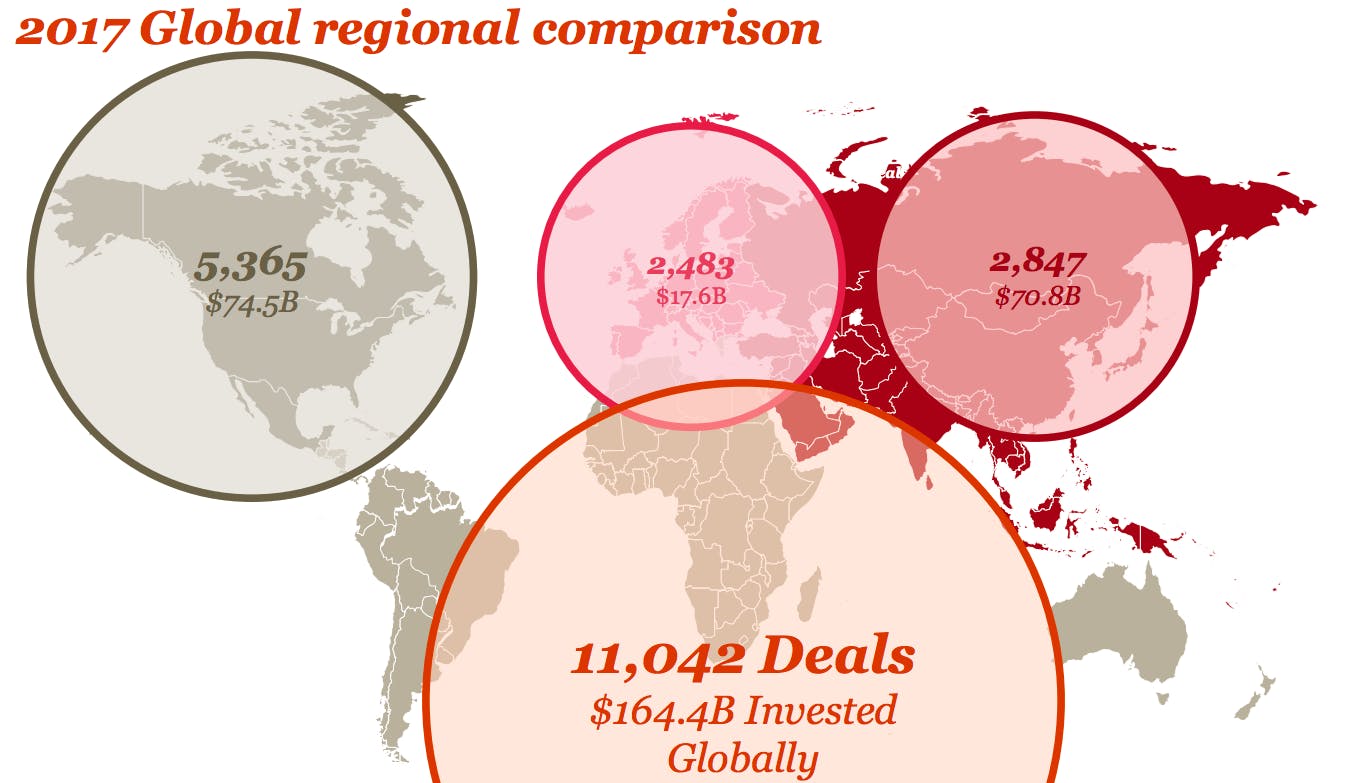

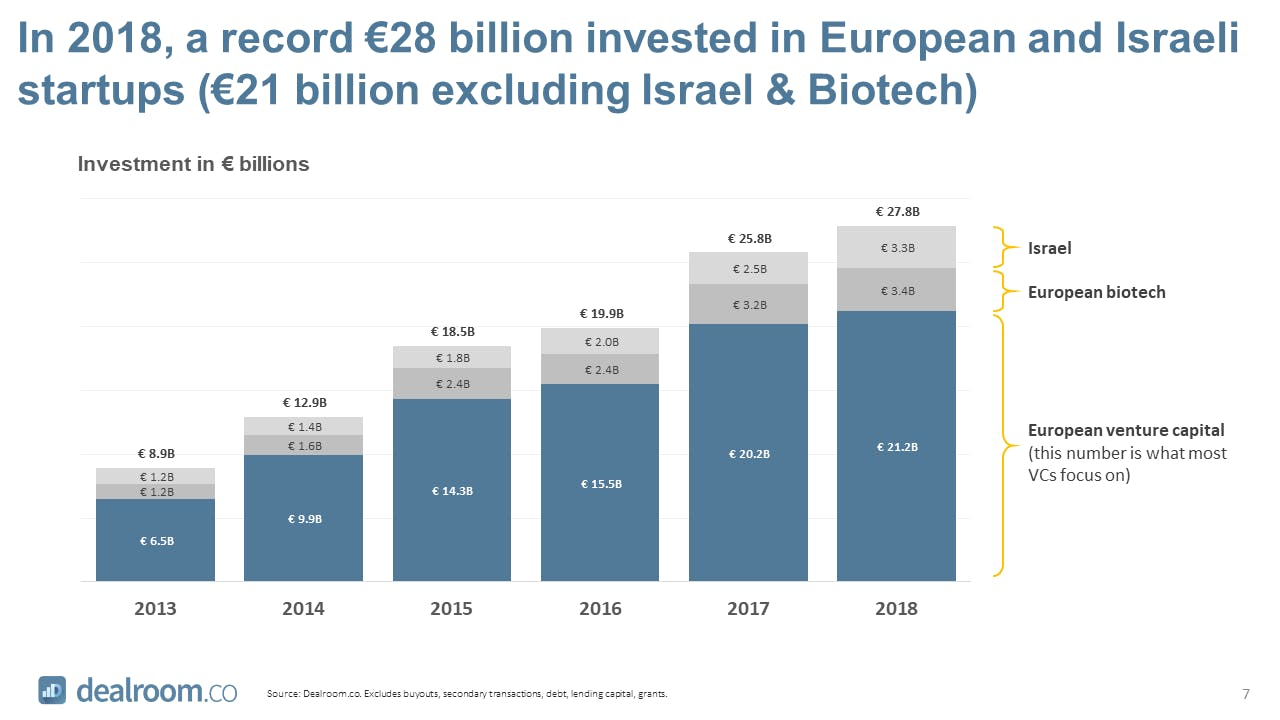

It starts with today's current landscape: Europe climbing to a strong 3rd place in VC investing, led by the UK. The US and China lead the way for the amount of capital invested, but the Old Continent is closing the gap.

In 2019 alone the amount of capital invested in European VC alone was $34.3B: on track to surpass $110B of capital invested since 2015 by this year.

Before 2014, however, money flowing into new ventures was hard to come by. Europe struggled for decades to go from $1B to about $5B of yearly invested capital, and then got stuck there for years.

The US, on the other hand, were racing ahead both in innovation and technology-related employment creation thanks to a solid Venture Capital industry. In terms of modern history, they are effectively the fathers of today's VC game and remain clear leaders to this day.

This was not always the case.

The Official Beginningsof VC

Harvard Business School professor Georges Doriot is generally considered the "Father of Venture Capital". He started the American Research and Development Corporation (ARDC) in 1946 and raised a $3.5 million fund to invest in US companies that commercialized technologies developed during WWII.

Georges Doriot

ARDC's first investment was in a company that had ambitions to use x-ray technology for cancer treatment. The $200,000 that Doriot invested turned into $1.8 million when the company went public in 1955.

Venture Capital was sought by risky startups needing lots of up-front cash, whether for research and development or for essential leaps in scale. Such financing seemed especially suited to proprietary technology, which was expensive, hard to seed into the market, and yet, if things went right, extremely lucrative.

Official finance history regards Fairchild Semiconductor as the first technology company to receive VC funding. It was funded by east coast industrialist Sherman Fairchild of Fairchild Camera & Instrument Corp.

Fairchild Semiconductor (1957)

Arthur Rock, an investment banker at Hayden, Stone & Co. in New York City, helped facilitate that deal and subsequently started one of the first VC firms in Silicon Valley: Davis and Rock. Davis & Rock funded some of the most influential technology companies, including Intel and Apple.

The Unofficial Beginnings of VC

In V.C.: An American History, another Harvard Business School professor, Tom Nicholas, proposes instead that whaling was the first industry where what we now call venture capital appeared: collecting large pots of money and using it to invest in young ventures, in the hope of guiding growth and generating huge returns.

Dispatching a whaling voyage would cost between twenty and thirty thousand dollars, a small fortune in the mid-nineteenth century, and an industry emerged to get these expeditions off the dock. Specialised agents in whaling-industry towns invested their own money, pooled cash from rich investors, did due diligence, and worked with captains to develop winning strategies and to plot uncrowded routes.

Whaling Vessel

In most cases, their efforts were fruitless: data from a couple of whaling ports in Massachusetts in 1858 suggest that fully two-thirds of returning expeditions were unprofitable; another study found that a third of the whale ships in the New Bedford fleet never made it home. A lucky outing, though, could return with a hundred and fifty thousand dollars in goods, a fortune several times the outlay, and for many investors this was enough to justify the risk.

In the mid-nineteenth century, New Bedford, Massachusetts, was the "Silicon Valley" of the whaling world and the richest city per capita in the United States --- if not in the world, according to one 1854 American newspaper. The US whaling industry grew by a factor of fourteen between 1816 and 1850, driving wealth, innovation and worldwide prominence for a country, the USA, that was only born less than a century before.

In Pursuit of Leviathan, a classic text on whaling economics, uncovers countless examples of innovation that both empowered and were empowered by this "VC approach" to whaling. They chiefly revolved around 4 areas.

A whale hunt, Courtesy: Nantucket Historical Association

First and most broadly, Americans sailed bigger and better ships guided by smarter ocean cartography and more precise charts. Second, a series of tinkering with harpoon technology led to the invention of the iron toggle harpoon. Third, innovations in winch technology made it easier to pull in or let out large sails, reducing the number of skilled workers needed to man a vessel. Fourth, whale captains were innovators in employee compensation. In the lay system, "every member of the ship's company from captain to cabin boy signed on, not for a wage or piece rate, but for a predetermined percentage of the value of the product returned," the Leviathan authors write. Savvy captains of the whaling barques were keen to aligning company interests, not unlike startup entrepreneurs today using stock options.

The individuals who organised these whaling voyages, the whaling agents, functioned much like venture capital firms of today. Although they raised most of their money from wealthy individuals, there are many records of blacksmiths and shopkeepers investing their savings with agents, in hopes of healthy returns. In pooling the capital of many members of the community and allocating it across multiple risky ventures, the agents filled an important role, not only for financing the voyages, but also for diversifying the risks that their investors faced.

Although there are some notable differences between the VC/startup and the agent/lay model, the latter was a clear preview of the stock option/venture capitalist structure of today.

The European Precursors

Venture Capital, so the story goes, was born and grew up as an "American thing" of the 20th Century. At first mainly funded by banks located in the Northeast, then moving to the West Coast after the growth of the tech ecosystem.

Tom Nicholas' book seem able to convincingly trace the industry roots before the beginnings of equity investments, all the way back to the 18th Century. Yet, it still looks like an all-American affair.

Was that the ultimate beginning?

Not quite.

Fra Angelico ─ St. Nicholas with the Emperor's Envoy and the Miraculous Rescue of a Sailing Vessel

Raymond De Roover, a Harvard historian, published in 1963 his classic The Rise and Decline of the Medici Bank (1397--1494), which opens with the statement that "modern capitalism based on private ownership" was invented by Italian merchants and bankers, by far the most active businessmen in the Middle Ages. Joint stock companies did not exist until the 1600s, "but the Medici Bank had foreshadowed the holding companies in certain respects."

The Medici Bank of Florence was the most important financial institution in 15th-century Europe. At its peak, the Medici Bank was the chief bank for the Roman Catholic curia, and it had branches in the major cities of Italy, as well as in London, Lyon, Geneva, Bruges, and Avignon.

It operated like a true investment bank of today's age, as well as like a merchant corporation with its own Venture arm.

The wool and cloth industries for example were the export mainspring of the Florentine economy in the 14th and 15th centuries. In 1402, the Medici Bank invested 3,000 florins, nearly one-third of its original capital, to finance a Medici family partnership to produce woollen cloth. In 1408, they "seed invested" a second and more successful shop of the same kind and some time later they invested to back a new Florentine silk workshop. The Medici further diversified their risk by engaging in the trade of a large number of commodities that included wool, cloth, alum, spices, olive oil, silk stuffs, brocades, jewellery, silver plate, and citrus fruit.

Marinus van Reymerswaele --- Money Changers

Marinus van Reymerswaele --- Money Changers

Their "merchant ventures" aboard galleys and ships were in many ways similar to the whaling expeditions of 18th and 19th Century America. Vessels had to be filled with goods, captains had to be paid and salesmen needed to reach international markets and fairs and try to sell their goods there. There was no guarantee this process would be successful, yet if it did it normally returned handsomely to both the salesman and the investor-merchant.

The Medici Bank was organised as a partnership, with the Medici family as the largest investor in the parent company. The parent company was the largest investor in the branch partnerships (often "limited liability partnerships") and functioned like a modern holding company. Managers' interests were kept aligned with those of the parent/investor by being paid a share of the profits as opposed to a fixed salary.

Bust of Giovanni di Bicci de' Medici by Romeo Pazzini

The founder of the Bank was Giovanni Di Bicci De' Medici, whose father was neither rich nor successful in business. His fortune begun by being admitted as a clerk in a distant cousin's bank, where he eventually rose to the position of branch manager in Rome. When his relative retired in 1393, Giovanni and his partner, Benedetto di Lippaccio de' Bardi, invested their own savings as well as externally raised capital into the business and took over the Roman branch. In 1397 they moved their business to Florence where Giovanni officially incorporated as the Medici Bank ("Banco de' Medici").

By the time of his death, Giovanni had accumulated enough wealth and power through his bank to be as important a figure as Italian royals, cardinals and politicians of his time. He was succeeded by his son Cosimo, who continued to grow the Medici Bank into the largest banking house of its time.

After Cosimo's death, his son, Piero, and his grandson, Lorenzo, had a much less steady hand on the branch managers and gradually lost their grip on the banking empire. The Bank eventually failed in 1492, when Lorenzo's son was ousted from Florence. By then, however, the Medici had contributed to the economic and artistic development of Florence into the craddle of Europe's Renaissance. Their championing of financial innovation, marchant and industrial venture endeavours, and artistic patronage brought about a time where humanity advanced significantly with a burst of new ideas, new inventions, and new art.

Financial Innovations, Arts and Venture Capitalism

In finance and business, the Medici perfected and popularised modern double-entry accounting. The method of double-entry bookkeeping works on the equation that 'Assets = Liabilities + Equity'. It meant recording both credits and debits, for an easier overview of what money the business has, and where. It helped bankers and merchants keep a more accurate account of their financial decisions and allowed them to control their portfolio of subsidiaries, merchant ventures and investments.

They also helped modern lending and banking develop across Europe through instruments such as the Letter of Credit and the Bill of Exchange. These agreements between banks (often different branches of the very same Medici Bank) involved the buyer's bank guaranteeing to pay the seller's bank at the time goods/services are delivered. They would be authorised to receive pounds in the London branch, for example, at 40 pence to the florin exactly 90 days after a deposit in Florence. The London branch of the bank would then turn around and find someone wanting to purchase florins in Florence, but at the rate of 36 pence to a florin (currencies traded in different rates home and away). This little difference of 4 pence per florin gave the cunning Medicis a 22% annual return. In the eyes of the contemporary theologian, this was a currency exchange rather than a sin, absolving them of the judgement of God, whilst making a tidy profit.

Lorenzo il Magnifico

In practice, they also invented the Middle Class. Before them, there was only distinction between royals and commoners; now, an extra class inserted itself into the economy. The Medici effectively became rulers of the state of Florence by leveraging economical and business power, even though they did not come from an aristocratic background.

The Medici also used patronage to foster talent. They patronised some of the most brilliant artists of the Renaissance, including Bernini, Michelangelo, Leonardo Da Vinci, and Botticelli. The Medici took calculated monetary risks to sponsor genius, which paid back handsomely when statesmen, popes and dignitaries exchanged favours and business opportunities to have one of these artists work for them.

Cosimo De' Medici

The Florentines (and especially the Medici) also looked to different cultures and the past for inspiration. They dispatched emissaries far and wide in search of prised ancient Greek and Roman manuscripts. In 1444, Cosimo de' Medici founded the first public library in Florence and gifted it a huge number of books and manuscripts. This too was an investment that helped his family raise to its privileged position of leadership in the city. He hand-selected those individuals who were given access to this laboratory of learning, and, through this social dynamic, he actively shaped the politics of the state.

The Medici were not the only merchant-bankers of their time to sponsor artists, seed new businesses, invest in entrepreneurial managers and take calculated bets in risky trade ventures or political sponsorship. They were the ones that took them the farthest, though.

Thanks to their business dealings and private sponsorship, they did not only succeeded at becoming one of the most powerful families of Renaissance Europe, they also empowered others (from artists to merchants and entrepreneurs) to innovate, trade and effectively take Europe out of the Dark Ages.

The Venture Capital Rebirth

The capitalist and the proto-VC traits that emerged in merchant-bankers like the Medici effectively turned into state-sponsored mercantilism and colonialism in the 16th Century.

Credit was then the chief means of financing business ventures and the state played a main role in most large-scale enterprises.

It would take over 200 years for Adam Smith's works and the industrial revolution to plant the seed for a new wave of venture-based capitalism, which would still, however, rely on credit way more than equity investing.

The only exception to this was the American whaling industry, which, as we saw, worked similarly to Florentine bankers' partnership ventures or to modern Venture Capital.

This was because the whole finance world had actually regressed to a state where it was difficult for external agents to track the internal dealings of a company due to lack of structured information systems. Also, the concept of limited liability had fallen out of fashion and most businesses carried unlimited liability for its stakeholders.

American office in 1900

This all changed when limited liability became the norm for corporations --- thanks to an 1811 law by the state of New York. It was soon adopted throughout the US, then Great Britain, and at a later stage by countries around the world. On the other hand, establishing a company's value and the monitoring of its operations and finances took the whole 19th century to improve to standards that could make equity investments meaningful. The cash register was not invented until 1879 and it was only at the beginning of the 20th century that Henry Goldman (the son of the 'Goldman' in Goldman Sachs) found a way to underwrite securities for companies that didn't own tangible assets of substantial value, such as retailers and manufacturers. His idea? Recording and evaluating their earning power.

Before World War II, therefore, banks and the public would begin to buy shares in or lend money to companies with tangible assets or a recurring revenue derived from a retailing business.

The problem is that technology-focused entrepreneurial ventures didn't fall into either category. They couldn't borrow from banks because their business model was unknown and they still had everything to prove. And they couldn't raise capital from the public because no financier could value them.

Lionel Pincus --- a precursor to Angel syndicate investing

This gap led to the emergence of private equity: because it was so risky, technology ventures were forced to rely on wealthy individuals. In some cases those were syndicated by a merchant banker, who co-invested with his clients. But those deals usually failed to generate enough money to finance very ambitious ventures --- except if they were carried out by exceptional financiers such as Warburg Pincus' Lionel Pincus.

By the late nineteen-twenties, one per cent of American families earned nearly a quarter of the United States' income and held half of its wealth. Many set up investment vehicles, some specialising in high-risk offerings. Laurance Rockefeller, a grandson of John D. Rockefeller, began putting "venture" money into untested aviation companies.

In V.C.: An American History, Tom Nicholas calculates that he could have made more in the stock market, but Rockefeller was adamant. "Venture capital endeavours are not for the impatient," he remarked. "Nor are they for widows and orphans or people who cannot afford to lose."

The US Government's Pivotal Role

In Secret History of Silicon Valley, author Steve Blank notes how the Roosevelt administration decided to tackle the issue of outsmarting German and Japanese military technologies with an unconventional approach: they gave up on enrolling researchers in the military in favour of allocating public funds to the best universities and technology companies in the country.

Claude Shannon at Bell's Secret Labs

At Harvard University and MIT in Cambridge, and at Columbia University in New York City and Bell Telephone Labs, secret research laboratories were inundated with public money and crowded with the best scientists in the country, all with one mission: to invent the new, cutting-edge technologies that would help the US regain the upper hand.

After the end of World War II, a new challenge was to convert the US industry from manufacturing weapon systems to manufacturing consumer goods.

A few wealthy families created their own investment firms to seize the opportunities brought about by the end of the wartime economy. The Whitneys founded J.H. Whitney & Co., the Rockefellers founded Rockefeller Brothers Inc. (later Venrock) and the Phippses founded Bessemer Securities. All those took investing in technology companies to the next level.

With those new family-funded firms, private equity and Venture Capital became more professional. Instead of acting as co-investors as did the old-fashioned merchant bankers, professional management teams took charge of sourcing opportunities, evaluating risks, and negotiating investment deals on behalf of their shareholders.

Modern Venture Capital

Our journey through history has finally circled back to the "official beginning" of Venture Capital: the post-war world of Georges Doriot's ARD (1946) and of Davis and Rock (1961).

Despite promising financial results, ARD ultimately ceased to exist due to its conflicting goals: it aimed both at sustaining financial performance and rebuilding the American economy to create jobs for the veterans.

Meanwhile, the West Coast was still managing to make it without venture capital. Frederick Terman, who headed the Harvard Radio Research Laboratory during the war, was back on the West Coast as the provost of Stanford University, which he intended to turn into a leading university in the sciences. To achieve that goal, Terman made it a priority to attract the budgets that the Department of Defence now allocated to advanced research in US universities.

Vannevar Bus, the father of advanced military research in US universities

In all practical terms, it was military procurement, both by the government and weapons manufacturers, that enabled the founding of the first entrepreneurial ventures in what was to become Silicon Valley.

To stimulate private investment into innovative new ventures, in 1958, the US Congress passed an act designed to encourage small-business investments and loans. If a small-business investment company could raise a hundred and fifty thousand dollars, the government would match those funds and lend more at a low rate, bringing the fund to at least four hundred and fifty thousand dollars --- nearly four million in current dollars.

In V.C.: An American History, we find quotes of early venture capitalists saying that they wouldn't have got into the game if it hadn't been for federal incentives. Venture Capital thus transformed from the pursuit of a few ultra-wealthy scions into a true profession.

In 1978, the Revenue Act was amended to reduce the capital gains tax from 49.5% to 28%. Then, in 1979, a change in the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) allowed pension funds to invest up to 10% of their total funds in the industry.

These changes, plus firms' embrace of limited liability partnerships, brought financial growth to the community that the incentives had founded. By this time, professional venture-capital portfolios began to repeatedly outperform the public markets.

As personal computing reached consumers for the first time, notably with the release of the Apple II, Venture Capital grew tenfold in the following years.

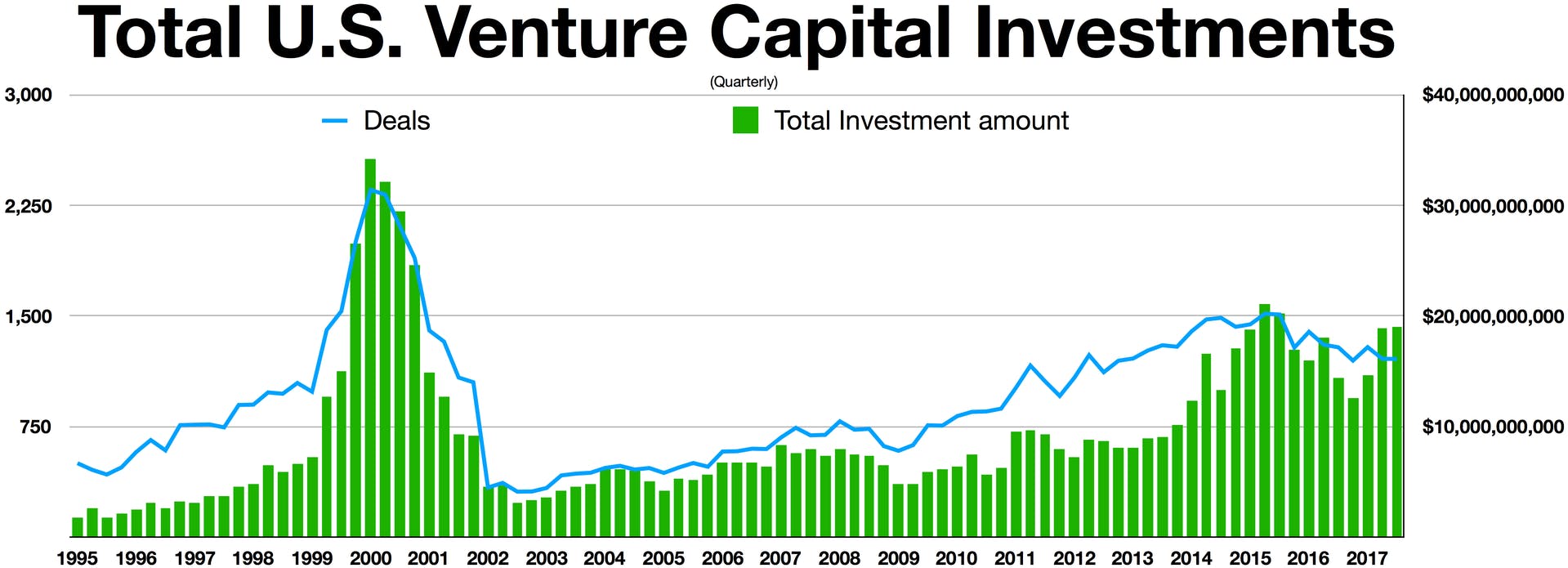

With growing returns from a now established VC sector and technology spreading into everyone's home, US investors became overtly bullish. Towards the end of the 90s, a craze around technology companies turned a growth period into a true and sudden boom. It was the now infamous 'dot com' bubble.

The Macintosh Team, 1984 (Left to Right) George Crow, Joanna Hoffman, Burrell Smith, Andy Hertzfeld, Bill Atkinson, Jerry Manock. Credit: © Norman Seeff

According to some estimates, funding levels during that period peaked at $119.6 billion. But the promised returns did not materialise as several publicly-listed Internet companies with high valuations crashed and burned their way to bankruptcy.

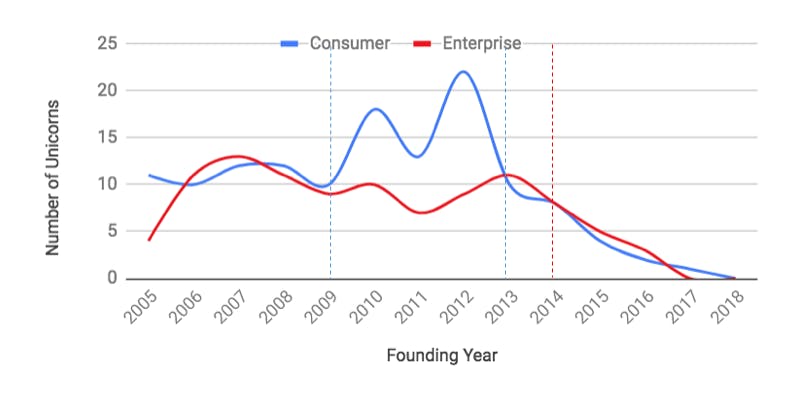

Despite the burst, VC had by then become a truly established and mature vehicle. The industry recovered and in the following decade it would contribute to the rise of household names like Stripe, Facebook and Netflix as much as of less know billion dollar innovators such as Palantir, Bloom Energy, and Okta. Meanwhile, 48% of dot-com companies survived through 2004, albeit at lower valuations.

As growth in the technology sector stabilised, companies consolidated; some, such as Amazon.com, eBay, and Google, gained market share and came to dominate their respective fields. The most valuable companies are now in the technology sector.

Total US Venture Capital Investments

Venture Capital continued to gain pace in the US and to produce both new technologies and even entire new economies. In the aftermath of the 2007--8 financial crisis, for example, startups like Airbnb, Bolt, Careem, Gojek, Grab, Lyft, and Uber grew out of bold VC financing to create multi-billion dollar value in a worldwide economy still shocked by the fall of the public markets. Their rise marked the beginning of what's become known as the "sharing economy" phenomenon.

Number of Unicorns Founded by Year (2005--2018) (CrunchBase)

Since its post-war inception, modern US Venture Capital investors seeked profits by backing innovators in evolving industries, often at the ground level, hedging the risks associated with mature companies ripe for disruption. Hence, the overwhelming majority of deals financed by venture capitalists today are in the technology industry. But other industries have also benefited from VC funding. Notable examples are Staples and Starbucks, which both received venture money. Venture Capital is also no longer the preserve of elite firms. Institutional investors and established companies have also entered the fray. For example, tech behemoths Google and Intel have separate venture funds to invest in emerging technology. Starbucks also recently announced a $100 million venture fund to invest in food startups.

With an increase in average deal sizes and the presence of more institutional players in the mix, venture capital has matured over time. The industry now comprises an assortment of players and investor types who invest in different stages of a startup's evolution, depending on their appetite for risk.

What about the rest of the world?

Despite overseeing the development of ancestral form of Venture Capital and Private Equity, Europe never developed a proper VC industry in modern times. As we have seen, Venture Capital in its contemporary form originated in the United States. Since then, American firms have been the largest participants in venture deals with the bulk of venture capital being deployed in American companies.

However, spurred by the American example, other economies decided to promote a professional enterprise-backing industry in their own territories. Therefore, over the last two decades, the number and size of non-US venture capitalists have been expanding.

2017 GLOBAL VC FUNDING --- Data from CB Insights and PWC

China

As an emerging economy, China started to develop its VC industry in the 1980s, though at a very slow pace. In The rise of venture capital centres in China: a spatial and network analysis, authors Pan and Zhao report that it was not until the late 2000s when the industry experienced a fast hyper-growth that catapulted it to being the 2nd largest VC market in the world.

Not surprisingly, governments were highly involved in setting up early VC firms in China. For instance, the National Research Centre of Science and Technology for Development was established in 1984 aimed at developing high-tech industries. More venture capital firms backed by state and local government were set up in the 1990s, most of them in national high-tech industry parks across the country. However, the development of domestic VC was stifled due to the lack of divestment opportunities, with no Nasdaq-like segment on the Chinese stock market.

Andy Yan Yan, chief managing partner of SAIF Partners, a Beijing fund created by Cisco Systems and Softbank Group

In contrast to domestic VC firms, foreign VC firms in China experienced rapid growth in the late 1990s and early 2000s, highly related to the strong stock market performance in the US. Many foreign VC firms that invested in Internet-related portfolio companies successfully exited via IPOs on overseas stock exchanges.

However, domestic VC firms had no access to IPO channels on either foreign or domestic stock exchanges. Many successful listings on overseas stock exchanges motivated China's policy makers to launch its own Nasdaq-like stock market segment. During this period, active foreign VC activities were extremely concentrated in several metropolitan areas in east China.

China planned to establish Nasdaq-like stock markets from the late 1990s. It was expected that the second board would be set up in Shenzhen in 2002. However, the bust of the dot.com bubble in the US's capital market delayed this development. In 2004, the SMEB was finally launched, providing an opportunity for domestic VC firms to divest in their portfolio firms through an IPO.

State-owned VC firms have become dominant in the rapid growth of the domestic VC industry in China since about 2004. In particular, China has evolved a tradition in setting up government-financed VC firms to support tech startups. In the meantime, privately-owned VC firms were also emerging, including spin-offs and spin-outs from established VC firms, stock-exchange listed firms and those set up by former government officials.

VC investments increased in 2006 and reached the first peak in 2007. After one year's stagnation, they started to grow again from 2009 at an unprecedented pace. Meanwhile, the number of VC-backed IPOs grew from 2005 and peaked in 2011. By the end of 2013, there were 516 publicly listed firms that were backed by VC firms. In China, VC-backed firms are highly concentrated in coastal regions, while less presence in the central and western part of the country.

Shenzen, prominent Hi-Tech Hub in China

Given the composition of the VC-backed listing firms, the institutions influences are more important than technology capacity in shaping the spatial and network patterns of VC activities related to domestic IPOs. VC in China (and in general in Asian economies) have been thought to be different from that in western economies due to th e different regulatory environment. In particular, the regulation of IPOs and the active involvement of state in capital markets and VC investments probably constitute the key institutional context to understanding domestic VC activities in China. The ongoing interests of governments of different levels in providing funds for VC firms might continue to shape the geography of VC activities in the country, just like it continues to shape the growth of the whole Chinese economy in general.

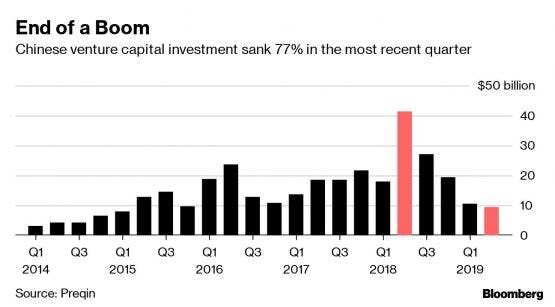

After 4 years of hyper-growth, the Chinese VC industry corrected in in 2019 and looks set for a period of slower growth and increased maturity

India

The first professinal venture capital firm known to be started in India was ICICI, wholly owned by the ICICI bank. They started giving funds to companies in the late 2000s as risk capital by modelling themselves in the style of US VCs. Their success attracted other players, both domestic and international.

2019 was a milestone year for the Indian VC industry, with $10 billion in capital deployed, the highest ever and about 55% higher than 2018.

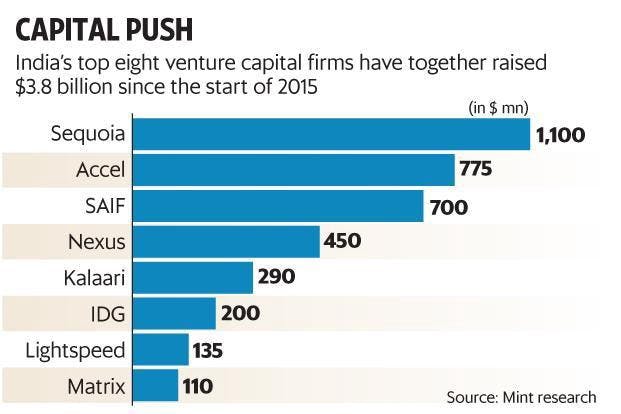

Foreign VCs with an office in India still account for most of the capital raised and deployed in the Indian ecosystem

Accourding to the India Venture Capital Report 2020 by Bain & Company, the Indian VC industry passed through three distinct phases over the past decade:

- Between 2011 and 2015, the industry experienced rapid activity growth (albeit off a small base) to support an evolving start-up environment. During this phase, multiple VCs entered and became active participants in India's economy for the first time.

- This initial, almost euphoric, phase was then followed by moderation between 2015 and 2017. The lack of clarity regarding exits made investors more cautious, and that shifted the focus to fewer and higher-quality investments.

- Over the past two years, however, the VC industry in India has been in a renewed growth phase, buoyed by marquee exits for investors, such as Flipkart, MakeMyTrip and Oyo; strong start-up activity in new sectors, such as fintech and software as a service (SaaS); and market depth in e-commerce.

Europe and Israel

While North America has historically dominated the modern Venture Capital industry, and despite Asia accounting for the greatest proportion of growth capital secured over the years, Europe's overall shares of venture and growth capital have increased recently in line with investors' growing interest in the region.

Attendees at SuperVenture 2020, source Sifted.eu

However, despite being similar to the US in terms of GDP, possessing a larger population, and pioneering a proto-VC industry already in the 15th Century, Europe still sits very far behind the US in terms of venture financing.

So, why has a comparable VC industry not grown in such a strong economy?

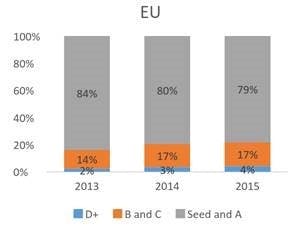

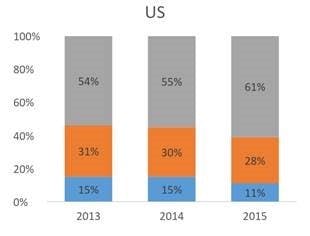

By analysing data from the late 2000s, it is possible to notice certain differences between the US and Europe. In particular, securing growth financing has historically been significantly harder in Europe compared to the US.

Despite being the cradle of capitalism and having witnessed a certain level of early stage private investment into private firms for centuries, Europe never developed a professional VC industry that could support long term company growth.

Due to limited late-stage funding, European companies have been historically forced to cut growth, reduce expense, and become profitable. Meanwhile, well-funded US counterparts continued to invest their sizeable funds into product and sales, allowing them to dominate their markets. Consequently European startup firms never reached their potential, whilst VC-backed companies in the US matured in the tech giants we are all familiar with, such as Apple, Amazon, Google, Facebook or Airbnb.

In short, the lack of mature VC players able to raise large funds and fund companies' growth-stage expansion prevented Europe from developing a mature VC industry in modern times. This lack of Venture Capitalists may in turn be explained by the lack of a central government in Europe that could mirror the funding and tax incentives for R&D and VC, which the US government implemented after World War II. Besides, trade barriers in the form of national frontiers as well as currency, language and cultural disconnect, made it harder for local startup companies to address a large user-base than it might have been for American startups.

With the creation of the European Union in 1992, the situation began to change. Non-English speaking children across Europe began to learn and practice English as a second language and trade barriers effectively disappeared. In 1994 the EU established the European Investment Fund (EIF), a European Union agency for the provision of finance to small and medium-sized enterprises through the investment in venture funds. In 2002, most of Europe adopted the Euro as a single currency. Over time, the EIF encouraged the development of national funds throughout the EU, which in turn joined the EIF in spurring the development of new VC firms.

As these new entities developed in the early 2000s and their track record became established, they were able to raise increasingly large funds to back private companies with larger cheques and a more patient growth capital. This allowed tech entrepreneurs in the late 2010s to "dare more" and focus on growth as opposed to rush for a quick acquisition or early profitability.

In 2008--2015, Europe-focused venture capital and growth funds collectively failed to raise more than €10bn in any year; however, 2017 marked the second consecutive year in which this figure was surpassed, and the industry has since grown not only in amount of money invested but also in the number of billion-dollar companies produced (so called "unicorns"). Over the years, venture capital investment activity in Europe has increased, and twice as many transactions were completed in 2016 than in 2009.

Just like in the US, not all the European states withnessed the same rate of VC growth and results. Mirroring Silicon Valley, London became the epicentre of the European Venture Capital growth, whilst other smaller centres developed across the continent and continue to accelerate their growth.

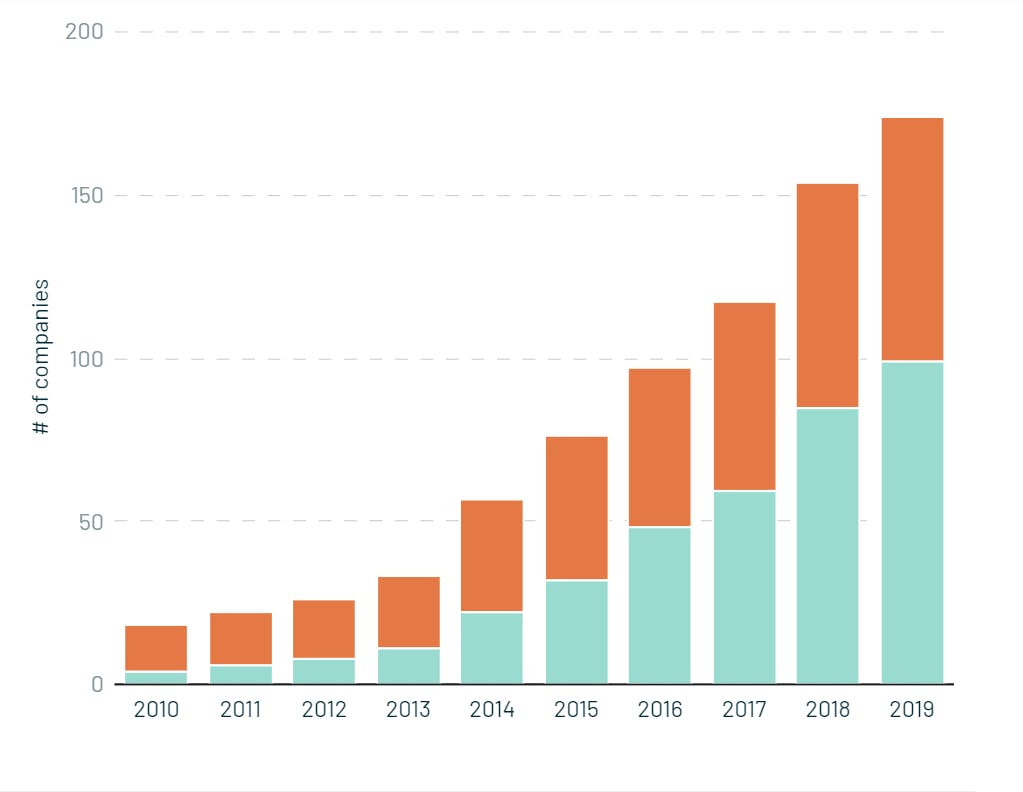

Number of VC-backed & non-VC-backed $1B+ European tech companies per year (cumulative) --- Source: Dealroom

In the years 2014--2019, capital invested in Europe has increased by 124%. Since 2018, this number has grown over 39%. There are now at least 174 European tech companies that have scaled to a valuation of more than $1 billion. Before entering this decade, that number stood at just 13, meaning Europe has seen over 13x increase in the number of companies scaling to this milestone.

The European VC growth also attracted oversea investors, which fuelled a further increase in capital available to startups and VC funds. Meanwhile, the number of exits and their size continued to increase. This meant that many former entrepreneurs could inject their new wealth back into the system, as well as raising further funds from private investors. A prime example of this is the London firm Atomico, founded by Skype's cofounder Niklas Zennstrom, which announced a new $820m fund just before 2020.

Overall, Europe seems on track to enter the 2020s with a stronger ecosystem with both room to grow and fundamentals to fuel such expansion. According to Crunchbase's 2019 "Key Trends" forecast, the European ecosystem could easily grow 4 to 5 times before reaching the levels developed in the US over the last century.

Geographically positioned near Europe, on the shores of the Mediterranean sea, Israel too deserves a note when discussing the development of Venture Capital. Israel's venture capital industry was born in the mid-1980s and has rapidly developed since. The first Israeli Venture Capital fund, Athena Venture Partners, was founded by Major-General Dan Tolkowsky, the past Chief of Staff of the Israel Air Force.

The success of the Venture Capital industry in Israel continued with Yozma (Hebrew for "initiative"), a government initiative in 1993 offering attractive tax incentives to foreign Venture Capital investments in Israel and promising to double any investment with funds from the government.

CyberTech in Tel-Aviv has become one of the world's most famous cybersecurity and hi-tech conferences of our age due to the strong local ecosystem

As a result of their efforts, Israel's annual venture-capital outlays rose nearly 60-fold, from $58 million to $3.3 billion, between 1991 and 2000. The number of companies launched using Israeli venture funds rose from 100 to 800. Israel's information-technology revenues rose from $1.6 billion to $12.5 billion.

By 1999, Israel ranked second only to the United States in invested private-equity capital as a share of GDP. It also led the world in the share of its growth attributable to high-tech ventures: 70 percent. According to the OECD, Israel is also ranked 1st in the world in expenditure on Research and Development (R&D) as a percentage of GDP.

Investments volume in Israeli startups grew by 140% during 2014--2018 and M&A transactions from US buyers provided for plenty of exit opportunities for Israeli VC investors. In particular, Artificial Intelligence (AI) is the field that raises most investments (17%) among all high technologies in Israel, which has become famous for producing hi-tech startups in fields such as Cybersecurity and applied Machine Learning.

With over 60 companies listed on the NASDAQ stock exchange as of 2020 and the highest "VC investment per capita" in the World, Israel managed to develop a significant Venture Capital system that continues to show strong returns for investors and to promote the development of innovative tech companies.

Israeli and European VC ecosystems keep growing and are increasingly connected

Conclusions

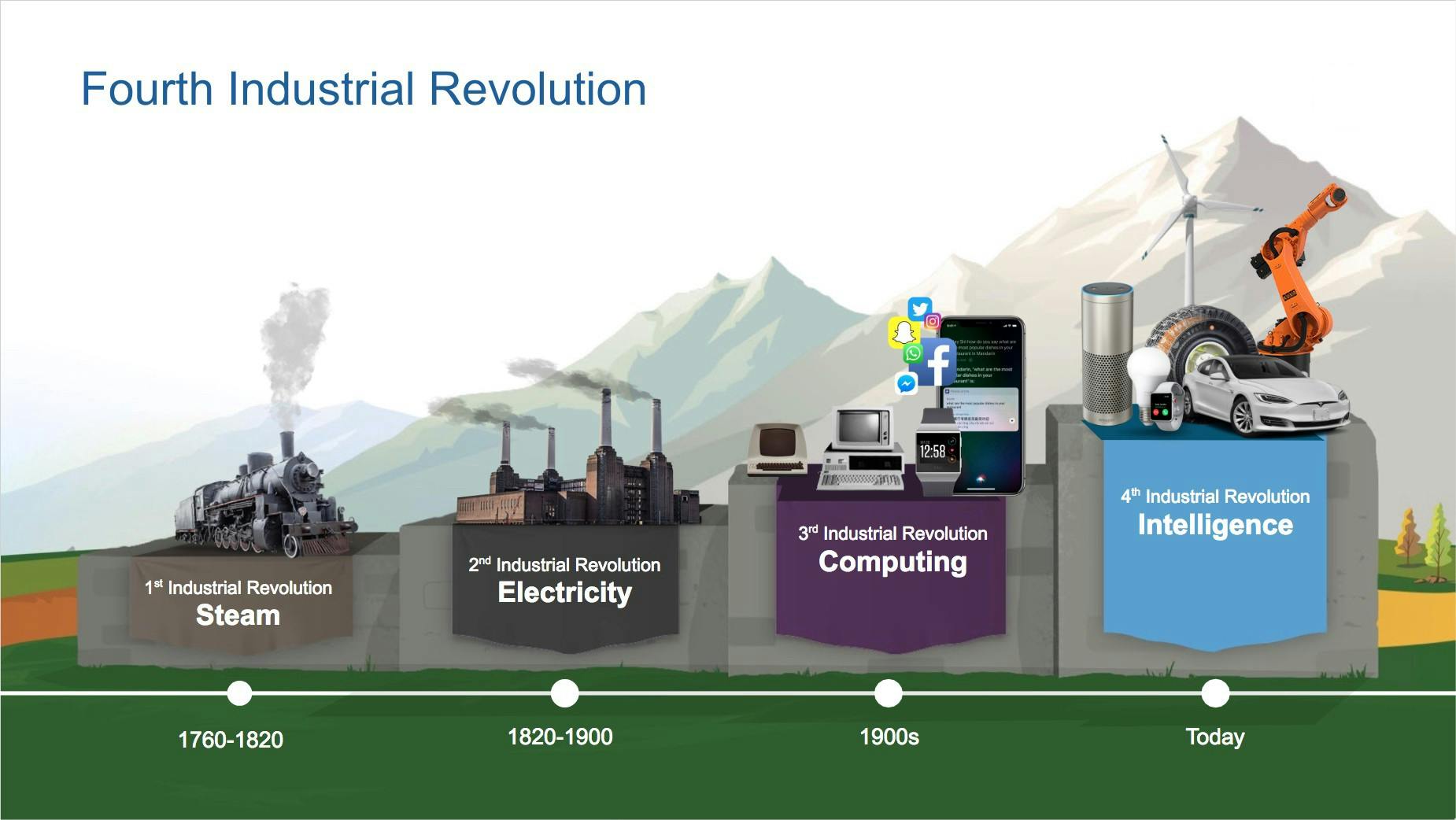

Whether it be cloud computing, machine learning, or Artificial Intelligence, emerging technologies are transforming many industries.

As we delve deeper into the 21st Century, we are all faced with challenges such as climate change and the adapting to a society where AI, genetic editing, remote working, self-driving cars and super-fast quantum computers will create both threats and opportunities.

Venture Capital investing has been for centuries the way wealthy families, corporations, institutions and even nations took charge of the "innovation and disruption game" rather than being a passive receiver.

In 15th Century Italy, Merchant-Bankers rising to powerful economical and political positions, like the Medici, developed the habit of serially investing in new businesses and in high-risk / high-reward trade ventures. They did so to both strengthen the economical power of their states (as well as their own families) and to diversify their asset allocation in a world that was changing fast. Wars, the Black Death epidemic, and a constantly changing economical and political landscape meant that hedging one's position from threats as well as capturing the opportunity offered by social, economical and technological disruption were one and the same thing.

In 19th Century America, investing in whaling ventures and their enterprising crews allowed an entire industry to develop and to reach a significant position in the global economy of the time.

After WWII, thanks to government incentives and the desire of wealthy industrialists to capture post-war opportunities, the US developed a systematic approach to Venture Capital investment for innovative enterprises. This helped the modern VC system to grow and was instrumental in the creation of many of today's highest valued companies, such as Apple, Alphabet, Intel, Amazon, NVIDIA and Facebook.

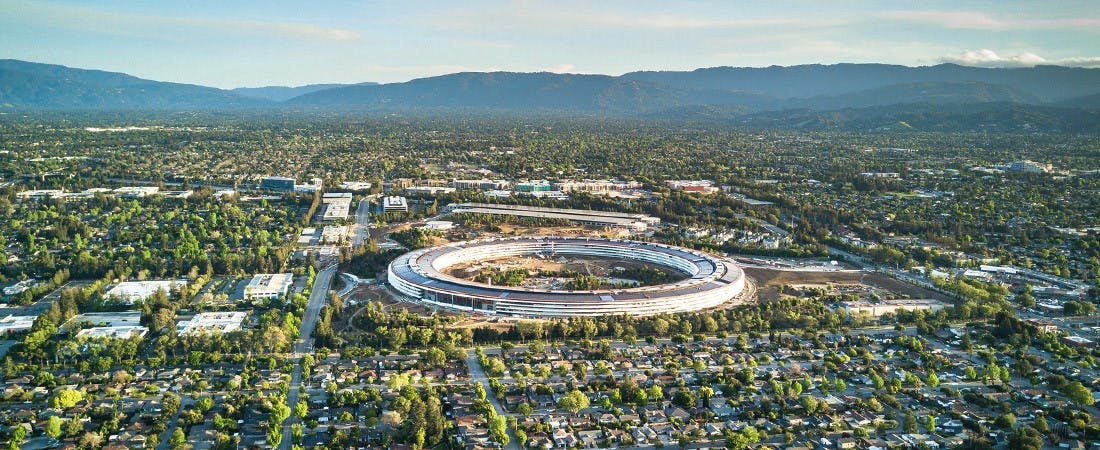

Silicon Valley --- the most advanced ecosystem of our time for startup enterprise and tech innovation is fuelled by Venture Capitalists' investments

When the emerging Asian economies of India or China grew their way into the aspiring superpowers they are today, they too decided to develop Venture Capital and spur innovation and private investment into new technologies and businesses. The results of such policies allowed the rise of tech giants in China, such as Alibaba and Tencent, or India's new unicorns such as Ola and One97.

Modern Europe did not managed to follow suit until the EU was formed and a centralised approach to promoting Venture Capital encouraged regulative changes, tax incentives and national programmes similar to what the US did post-WWII. Today Europe, including the now EU-exiting Britain, is raising fast to a position where a more mature VC ecosystem drives both high returns for investors and the development of new technologies and innovative businesses.

Due to its proximity to Israel, which developed a significant VC industry of its own, the two systems developed close ties and together account for a significant and growing slice of the worldwide VC market.

Where is this, now global, industry heading to next?

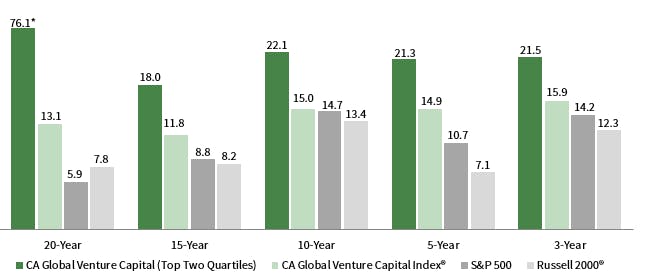

Venture Gapital has generated compelling returns relative to public markets, both in recent years and over long-term time periods.

As of June 30, 2019 - Global Venture Capital Periodic Rates of Return (%) (Cambridge Associates)

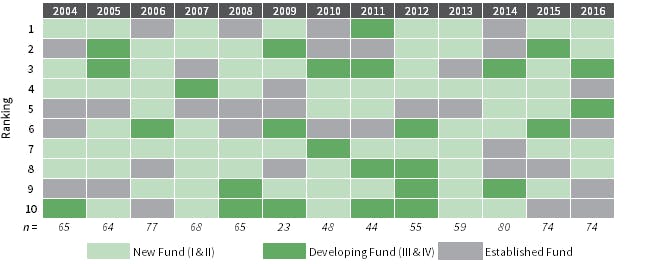

Meanwhile, the return and risk profiles of VC investing have changed, as today's market is not the same as 20 years ago. According to data collected by Cambridge Associates, broad-based value creation across sectors, geographies and funds means success is no longer limited to a handful of (often inaccessible) fund managers. Besides, top returns are not confined to a few dozen companies in Silicon Valley. In today's VC ecosystem, new and developing fund managers consistently rank as some of the best performers, whilst an increasing numbers of startup ecosystems throughout the world have the capacity to sustain mature and profitable Venture Capital investments.

Ranking, as of June 30, 2019 - US VC Funds by Vintage Year - Based on Net TVPI (Cambridge Associates)

Yet, when put into context, the amount of money raised in VC still represents a tiny fraction of the market value of the industries being disrupted by many venture-backed companies, and a fraction of the total addressable markets of emerging business categories being created by VC.

In 2018 Global VC stood at $340 billion net asset value (NAV), which was less than 0.5% of the $85 trillion in global equity valuation.

London's Old Street Roundabout ---One of the new global VC hubs that aim to rival the US Silicon Valley in the 21st Century

Even from our UK perspective, at Silicon Roundabout Ventures in London, we cannot but notice how an increasingly globalised VC and startup ecosystem is key to unlock opportunities out of 21st century challenges...

Just like the Renaissance merchant-bankers, the American whaling communities, and the post-war US venture capitalists, today's VCs are called to scout and back inventive entrepreneurs that can turn the global challenges of our time into new opportunities.

Originally published on SiliconRoundabout.tech on March 16th 2020 [edited 02/01/2022]